The holidays are coming up, so Shub and I thought we'd share a wishlist. Not for ourselves, but for what we wish founders would tell us during pitches. Among the two of us and our colleagues, we've reviewed many thousands of pitches at Foundamental. Maybe 20,000 in total. And across all those conversations over the years, there are specific things we prefer to learn, but rarely do. So here it is. Our holiday wishlist of things Shub and I wish more founders would specifically target us with about the fundraising process before they walk into our office.

This Week On Practical Nerds - tl;dr

A tactical six-month execution plans before you raise capital

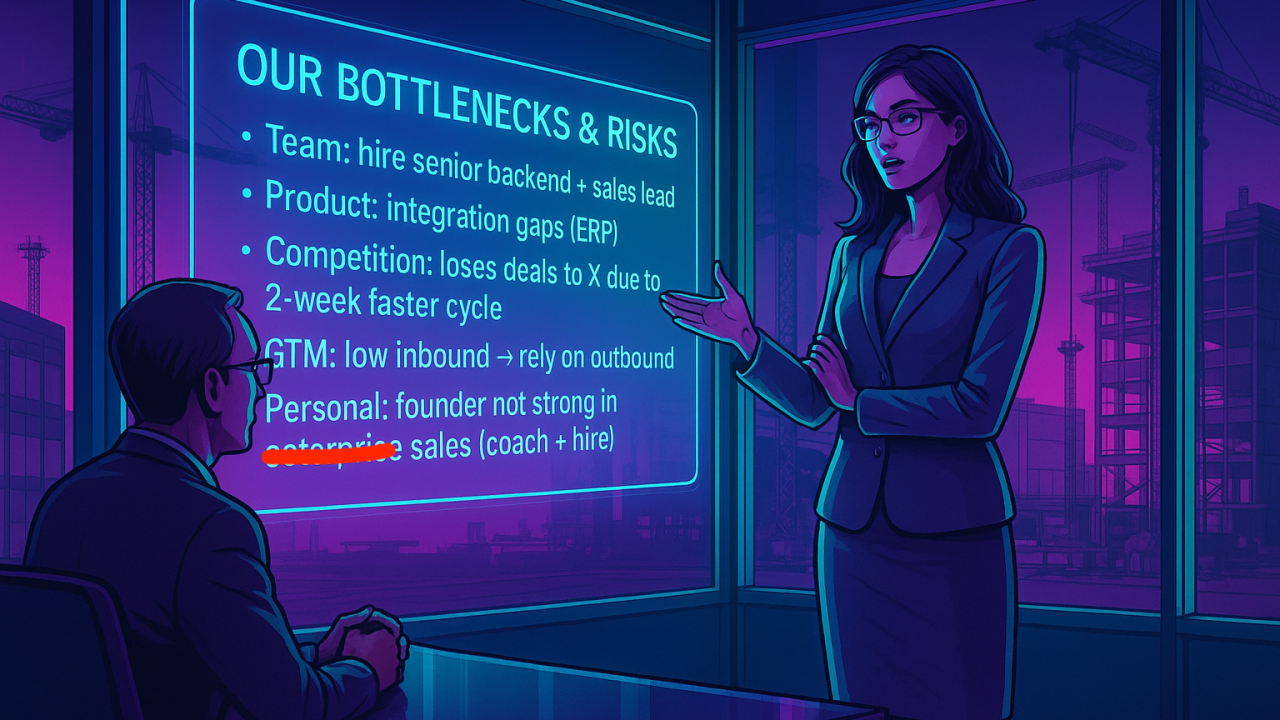

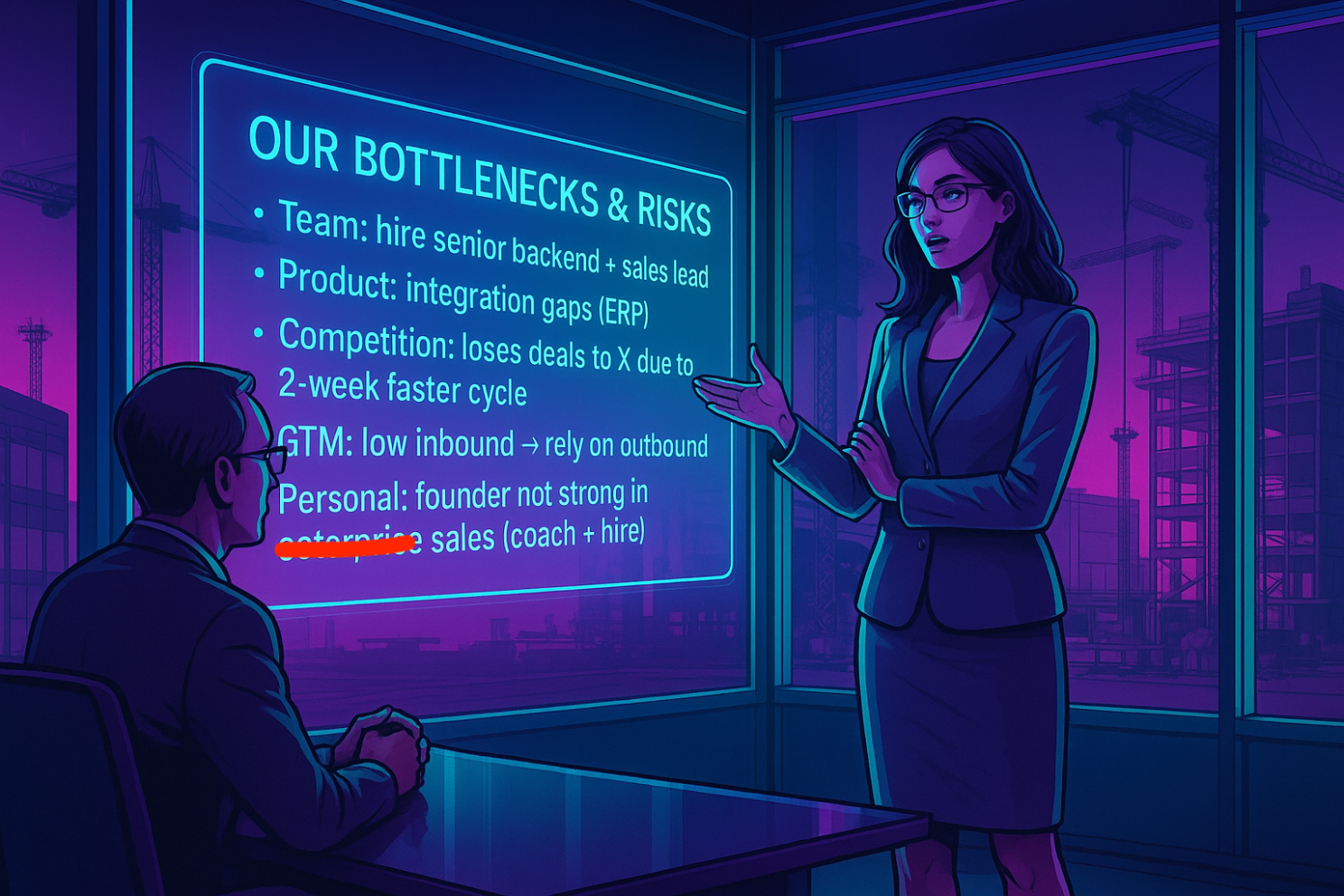

Obsess with bottlenecks, especially weaknesses in yourself and competition

Stay connected to primary information through founder-led sales activities

We Like Primary Knowledge

🎧 Listen To This Practical Nerds Episode

A tactical six-month execution plans before you raise capital

The gap between vision and execution planning

This is our number one. The thing we wish we could see but almost never do.

A founder walks into our meeting. Grand vision? Check. Market size? Looks promising (we love initial niches, so market size is rarely a sticking point initially for our taste). Team? Maybe, let's give it a shot.

Then I ask what I consider a pretty straightforward question: what exactly will you do in the next six months?

You would be shocked how rarely the response is clear.

What Shub and I hear too often. "That's why we're raising money. To figure it out."

In my experience, out of those 10,000+ companies we've collectively met, I'd say fewer than ten presented truly tactical execution plans. Shub guessed it might be low double digits when I pressed him on the numbers. It's shockingly rare.

I'm not talking about strategic frameworks or high-level roadmaps. I mean actual tactical plans with the kind of specificity that's almost painful to write down.

Let me tell you what I mean by tactical. If you're building a neobank for contractors like Faktus, which recently raised 56 million in equity and debt, you need to define your underwriting process before you raise. Not just the concept of underwriting. The actual granular process. Which specific data points you'll collect. How you'll weight them. What your approval thresholds are. The exact sequence of steps. Painful stuff.

In my view, this level of detail should exist for hiring. For sales. For marketing. Not "we'll do content marketing." Rather: these three conferences. These three booth locations at each one. This exact poster design. This specific headline on that poster. Most founders recoil when I push for this level of granularity. They seem to think it constrains them. They want optionality.

Yet what Shub and I have observed actually happens most often. You raise money without that tactical plan. Then you spend months after the raise building that plan. You've lost momentum. You've burned runway. You've wasted opportunity cost. We've seen this pattern play out dozens of times.

Why wait if you are going to need it anyway?

The hallmark responses tell me everything I need to know. When I push on six-month specifics, founders say things like: "But you have to remember the vision" or "That's why we're raising." Both responses signal the same thing to me. The founder hasn't done the work yet.

Some founders counter with experimentation. "We'll run experiments to find out." That sounds reasonable on the surface. But in my opinion, experiments should test a thesis, not replace one. It's the difference between research and development. If you're raising money just to run directionless experiments, I'd argue you're confusing founder work with luck.

The distinction matters enormously in my experience. A thesis-driven experiment says: "Based on three customer interviews and two competitor analyses, we believe underwriting approach A will convert 30% better than approach B. Here's our three-week test plan." A directionless experiment says: "Let's try some stuff and see what works."

So I asked Shub, why do you think founders delay this tactical work? His honest answer resonated with me: it's hard. Getting granular requires extensive primary research. Fact-finding. Customer conversations. Competitive analysis. Writing it down creates accountability. You're committing to a plan you might be questioned about later.

Shub's hypothesis is that many founders prefer pushing this grunt work until after fundraising. They want breathing room. They want optionality. But I think this misunderstands the entire point of preparation.

I like to use this metaphor: Think about physical fitness. There's only one way to get in shape. Bring your body to a gym and work out. Your mind suffers through the inertia. Your mind finds excuses. But your body must do the work. No shortcuts exist.

Founder planning works identically in my view. Your brain must do the mental exercise of tactical planning. You can't delegate it away. You can't buy a device that stimulates your abs while you sit on the couch. Remember those shopping channel gadgets from the 90s? That's what it looks like to me when founders delegate their tactical thinking to future hires.

The best founders Shub and I have worked with? They already have their six-month plan in motion before they raise. The fundraise accelerates execution, it doesn't initiate it. This communicates two critical things in my opinion. First, you're mission-oriented, not fundraise-oriented. Second, your plan has credibility because you've already started executing it.

In what I'd consider an ideal scenario, you spend three to six months before founding getting so tactical that when you show investors your execution plan, their reaction is: "This is the most actionable thing I've ever seen." That reaction almost never happens in my experience. But when it does, those founders stand out dramatically.

In our experience, the founders who succeed (big or small !) don't wait for money to build their execution plan. They build the plan, start executing, then raise money to accelerate what's already working.

Acknowledge bottlenecks openly, especially weaknesses in yourself and competition

How can founders identify what's actually blocking progress?

Shub and I did an entire episode on bottlenecks before. But the concept deserves repeating because we see founders resist it so consistently.

In my experience, a bottleneck can live anywhere. In you as a founder. In your team structure. In your product architecture. In competitive dynamics. In customer acquisition channels. The specific location matters less than the willingness to identify it.

Here's a basic test that Shub and I see most companies fail. We ask about competition. The response? Almost always dismissive in our experience. "They're not really competition because they focus on enterprise and we focus on mid-market." Or "Their product is outdated." Or "They don't understand the space like we do."

These responses, in my view, avoid the uncomfortable truth. Competitors exist. They win deals you wanted. They solve customer problems. They occupy mental space in your category. Dismissing them doesn't make them disappear.

What I'd consider a mature founder response sounds different. "Yes, competitor X wins about 40% of deals we both compete for. They win because their sales cycle is two weeks shorter due to pre-built integrations we lack. That's our current bottleneck. Here's our three-month plan to close that gap."

Notice the difference? One response deflects. The other acknowledges, quantifies, and addresses.

The same pattern shows up when I ask about founder weaknesses. How many founders volunteer what they're not good at? How many proactively explain why they might not be the right fit for their own venture? In my observation, extremely few. Maybe one in a thousand.

But I believe acknowledging the bottleneck is the only path to removing it. If you pretend competitor X doesn't matter, you'll never build the features that neutralize their advantage. If you pretend you're great at sales when you're actually mediocre, you'll never hire the sales leader who fixes that gap.

The language matters too. Shub and I almost never hear founders use the word "bottleneck." Even using different terminology, I'd say maybe one in a thousand founders shows real obsession with identifying constraints.

Here's how I test for bottleneck thinking. I ask any founder: "What stands between you and your next quarter's objectives?" Watch what happens. In my experience, about 99% of founders answer with resources. "We need to hire three engineers." "We need another $2 million in runway."

But that's not answering the question in my view. Resources aren't bottlenecks. Resources are what you use to remove bottlenecks. The real question is: what specific constraint would those three engineers address? What exact problem would that $2 million solve?

I think the human brain defaults to resource requests because resource requests feel safer. They don't require admitting weakness. They don't demand uncomfortable self-reflection. But they also don't drive actual progress in my observation.

Here's something Shub pointed out that I found really insightful. Successful repeat founders behave completely differently. Second-time, third-time founders who've been through hard journeys? They lead conversations with weaknesses. They volunteer bottlenecks. They discuss what might not work.

Shub's hypothesis, which I agree with: these founders learned the hard way. They probably wish someone had forced them to confront bottlenecks earlier in their first company. They could have saved themselves enormous heartache. So in their second innings, they front-load that honesty.

Even when you can't immediately remove a bottleneck, I believe knowing it exists changes everything. It reshapes priorities. It informs strategic choices. Sometimes acknowledging a bottleneck reveals you're in the wrong market entirely.

I like saying: you should win against competition through strategy, not by competing. That philosophy starts with bottleneck awareness in my view. You can't strategize around a constraint you refuse to acknowledge.

The fitness analogy applies again. Imagine you're working out. A certain exercise feels too strenuous. The bottleneck approach? Figure out how to improve performance on that specific exercise. Address the weakness directly.

What I see as the more common approach? Skip that exercise. Do something else. Pretend everything is great. Eventually, that weakness compounds into a serious limitation.

There's a saying I always remember: pain sits between what you are and what you want to become. In my experience, founders who embrace that truth build better companies.

In my observation, bottleneck obsession separates founders who actually improve from founders who just stay busy. The difference isn't subtle.

Stay connected to primary information through founder-led sales activities

Should founders continue doing sales after hiring a team?

I want to be clear upfront. This point reflects more of my personal taste than universal law! Different approaches to company building can succeed. But I strongly believe primary information drives prime decisions. And as a founder, making prime decisions is your actual job. Not fundraising. Not hiring. Decision-making.

Yesterday I was on a monthly catch-up call with one of my portfolio founders. He mentioned something casually. His team implemented a new sales enablement tool. The tool automatically records customer calls with permission. Nothing revolutionary yet.

Then came the insight that really impressed me. He said: "I made it a habit on my morning runs to listen to sample customer conversations our sales team is having."

That stopped me in my tracks. This founder leads product and technology. He's not the sales leader. Yet he's personally consuming raw customer conversations during his morning exercise. Think about the information quality that provides for product roadmap decisions. I find it exceptional.

In my observation, most founders transition away from this behavior. They delegate information collection. They prefer filtered summaries. Sometimes the intention seems good. They think delegation is more scalable. They want to trust their team.

But I believe filtered information produces filtered decisions. When you only receive summaries, you miss the nuances. The customer's hesitation. The specific language they use. The problems they mention but don't emphasize. These details shape great products in my experience.

I think the mindset that avoids primary information often comes from self-promotion. Founders start seeing themselves as CEOs rather than founders. They elevate their role. They think hands-on work is beneath them now.

But in my view, they've actually demoted themselves. They've removed themselves from the information flow that enables good decisions. In what I'd call high-performing organizations, the person with the best information makes the decision. If you delegate all information collection, you're implicitly delegating decision-making authority.

Shub pointed out that this pattern plagues venture capital firms too. Fourth, fifth, sixth generation partners at legacy firms. They go part-time. They stop seeing deals directly. But they still want to sit on investment committees. They want decision-making authority without information collection responsibility.

It makes no sense in my opinion. That's why I think Benchmark's structure works so well. Either you're all in with full information access and decision authority, or you're all out. No middle ground exists. From a succession planning perspective, I very much subscribe to this philosophy.

The same principle applies to founders in my view. You're a capital allocator. Someone trusted you with money expecting returns. They allocated capital to you because they believe you can generate better returns than alternative investments. That makes you an allocator.

I believe capital allocation requires primary information. You can't allocate effectively based on summaries and filters. You need direct exposure to customers, competition, market dynamics, and execution realities.

In my opinion, founder-led sales should continue post-IPO. Obviously on a sample basis. Obviously balanced with other responsibilities. But the practice shouldn't stop. Look at Fortune 500 CEOs. Take an educated guess which ones still do sales. Which ones stay deeply connected to product.

Jensen Huang at Nvidia. I'd bet yes. Alex Karp at Palantir. High likelihood in my view. How many others? Maybe 10% of Fortune 500 CEOs maintain this practice. I'd bet strong correlation exists between those who do and their companies' performance.

The reason this practice remains rare in my observation? It's hard. Listening to customer call recordings on morning runs requires discipline. It requires acknowledging that understanding your market demands continuous work. It's easier to delegate. It's more comfortable to receive executive summaries.

But I don't think comfort builds great companies. Primary information does. Sample-based exposure at scale works fine in my experience. You don't need to join every customer call. But you need some regular direct exposure. Without filters. Without summaries.

In my observation, many founders realize this too late. They wake up three years in and discover they've lost touch with their market. The filtered information they received painted an incomplete picture. Critical insights never reached them because someone downstream decided those details weren't important enough to escalate.

Here's a bonus insight Shub raised that I think connects to primary information. Many founders forget they're capital allocators. Burn isn't just spending. It's capital allocation. Every hire, every marketing dollar, every office decision. These are allocation choices that should generate returns.

I see founders often treat burn mechanically. They raise $10 million. They plan to last 18 months. They reverse-engineer monthly burn. Then they spend to that number. It's recipe-following, not capital allocation in my view.

Recipe-following assumes your situation matches the template. It assumes 18-month runways make sense for your specific market, product, and team. It assumes the default hiring plan applies. These assumptions often prove wrong in my experience.

What I'd call real capital allocators think differently. They ask: what return will this dollar generate? If I spend $200,000 on this hire versus this marketing channel, which produces better returns? These questions require primary information to answer well.

The mental shift sounds simple but proves difficult. When you raise money, you're not receiving free capital. You're selling ownership. You're trading shares for cash. Those shares have value. You're letting go of something valuable to receive something else valuable.

Think about trading Pokemon cards. You wouldn't consider the money you received as "free." You traded something you valued. I believe fundraising works identically. Once you internalize that the money came at a cost, you naturally want to earn returns on it.

This mindset isn't universally obvious in my experience. Shub and I agree that the venture industry doesn't help. Incentives on both sides push toward different objectives. VCs often optimize for deployment speed rather than return quality. Founders often optimize for growth metrics rather than capital efficiency.

In my view, primary information isn't optional for founders who want to make consistently good decisions. It's the foundation of everything else.

We Like Primary Knowledge

Based on what Shub and I have observed across thousands of pitches, here's what I believe separates exceptional founders from the rest.

Build tactical execution plans with painful specificity before you raise capital. Your six-month roadmap should already be in motion, not waiting for funding to begin. This means doing the primary research, customer interviews, and competitive analysis that most founders postpone until after their raise. In my experience, the best founders make investors react with "this is the most actionable plan we've seen" rather than "interesting vision, but what will you actually do?"

Embrace bottleneck obsession in everything you evaluate. Your own weaknesses, your team gaps, your competitive disadvantages. Name them specifically. Quantify them honestly. Address them systematically. I believe acknowledging a bottleneck is the only path to removing it, and sometimes that acknowledgment reshapes your entire strategy in productive ways.

Maintain direct exposure to primary information throughout your company's growth. Stay in sample customer calls. Read unfiltered feedback. Experience your product alongside users. This isn't about mistrust or micromanagement in my view. It's about having the information quality required to make prime decisions as a capital allocator. Because that's what you are, whether you think of yourself that way or not.

These three practices compound over time in my observation. Tactical planning forces bottleneck discovery. Bottleneck obsession requires primary information. Primary information improves tactical planning. Founders who master this cycle build companies that move faster and more deliberately than competitors who skip these uncomfortable steps.

You Can Find More Analysis On The Practical Nerds Podcast

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/1Q86tEwusNGwAmRdDqjFL4

Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/de/podcast/practical-nerds/id1689880222

Foundamental: https://www.foundamental.com/

Subscribe to the Newsletter: https://www.linkedin.com/newsletters/practical-nerds-7180899738613882881/

Companies Mentioned

Faktus: https://faktus.eu/

Nvidia: https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/

Palantir: https://www.palantir.com/

Follow The Practical Nerds

Patric Hellermann: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aecvc/

Shub Bhattacharya: https://www.linkedin.com/in/shubhankar-bhattacharya-a1063a3/

#VentureCapital #StartupFundraising #FounderMindset #CapitalAllocation #TacticalExecution #BottleneckThinking #PrimaryInformation #AECS