I know: you thought the series on new business models in AEC-tech was over with my last article on "OaaS" and "Cloud Manufacturing".

Well.. I thought so, too.

But upon deeper reflection, I came to the conclusion that one last model was worth talking about: HeSaaS (Hardware-enabled Software-as-a-Service).

I've heard this term for the first time some years ago, right at the beginning of my journey as an investor. But since then, I've rarely come across it again. Which is a shame, since the model can work wonders in Construction-tech, hence why I want to share some thoughts on it.

Before we dive in, just a reminder to also check out the previous articles in the series, in case you missed them. You can find Part 1 (Vertical AI roll-ups) here, Part 2 (Franchising and "Business-in-a-box") here, and Part 3 ("OaaS" and "Cloud Manufacturing") here.

Time to dive in!

Hardware as a wedge, software as a lock

For the longest time, the construction industry has been largely perceived as a technological laggard and overlooked by entrepreneurs in favor of "sexier" (and more readily digitized/digitizable) sectors. Yet, slowly but surely, SaaS finally arrived at the construction site, trading its Silicon Valley sneakers for steel-toed boots and proving that even the most analog industries can't escape digital transformation (the extent to which this has been successful is debatable). The past years have seen an explosion of software solutions targeting the AEC space, and a good influx of funding too ($37Bn in ConstructionTech as a whole over the past 10 years, according to Tracxn).

This boom, however, has created its own set of problems. The market is now saturated with a dizzying array of point solutions and specialized applications that solve one specific problem but often fail to communicate with each other. This fragmentation forces professionals to juggle multiple, incompatible platforms, leading to redundant data entry and new workflow inefficiencies. This is, however, a topic for another day. The more relevant (to this article) problem and implication from the proliferation of software is that most of these pure-play SaaS companies face mounting business challenges: it's really hard to differentiate yourself from 10 other alternatives in an increasingly crowded market. Software fatigue, slowing down adoption, certainly doesn't help. And besides, one might think that it is a bit pretentious to think that bit-based software can be the "magic cure" for inherently atom-based construction issues, without any connected hardware that captures data and/or acts on it.

It follows that, in this environment of low individual value and high commoditization risk, a more robust and defensible business model is not just an advantage, but rather a necessity for survival and long-term success.

Enter: Hardware-enabled Software as a Service (HeSaaS).

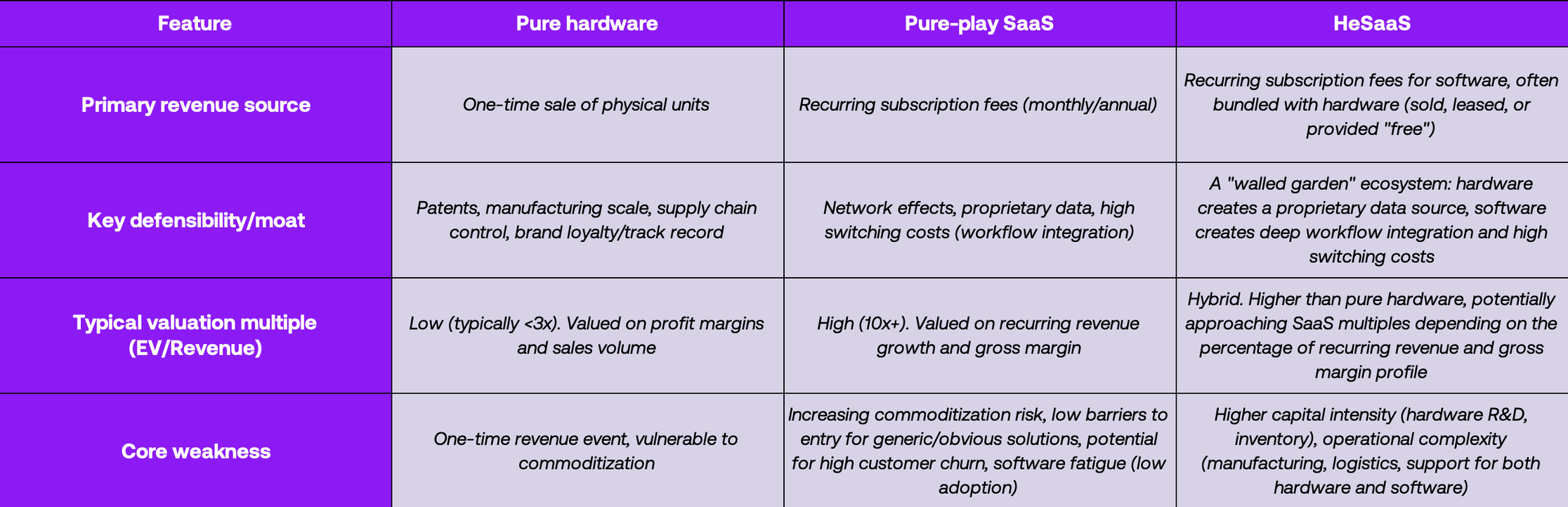

As the name suggests, you start with a piece of specialized, high-performance hardware. It's important that this is not a commodity (easily replaceable) device, but rather a differentiated tool that solves a critical, physical workflow problem significantly better, faster, or cheaper than any existing alternative - that is, assuming that there actually is any: in the best case, you will operate in a space hidden enough that your competition is mostly "indirect" substitute products. This superior (or even totally novel, but very much needed) physical-world performance is the wedge used to acquire new customers.

What transforms this from a simple hardware sale into a more powerful and resilient business model is the creation of a true "walled garden" ecosystem. Here's where software comes into the picture: it's your customer lock-in tool and your recurring revenue-generating machine. Indeed, ideally, the hardware's primary function is to act as a proprietary data-capture device that generates a unique stream of information (e.g. a real-time measurement) that is exclusively processed, analyzed, and made actionable by the subscription-based software platform you also provide. This creates a "walled garden" where the value of the hardware is fully unlocked only through the software, and the software is useless without the data from the hardware. This tight integration also significantly improves workflows and provides a user experience that "patched" solutions (generic off-the-shelf hardware paired with third-party software) simply cannot replicate. Besides, the software platform generates high-margin, predictable, recurring revenue, transforming a one-time hardware sale into a long-term (sticky) customer relationship (who doesn't love that?).

This deep operational entrenchment clearly creates formidable switching costs. A customer who has integrated the HeSaaS solution into their core processes (e.g relying on its data for quality control, scheduling, reporting, etc.) cannot easily switch to a competitor without disrupting their entire workflow and/or losing precious data accumulated over time.

From a business model perspective, HeSaaS transforms the economics of both customer acquisition and retention. The upfront hardware sale or lease helps offset acquisition costs while ensuring a committed customer relationship from day one. But the real prize is the recurring software revenue that follows: high-margin, predictable subscription fees that VCs (and public markets) value far more than one-time hardware sales.

Ultimately, this model systematically addresses the inherent weaknesses of the standalone business models it combines. It circumvents the low(er)-margin, one-time-sale nature of traditional hardware businesses while mitigating the growing risk of commoditization faced by pure-play SaaS companies. The integrated hardware component of a HeSaaS model provides a tangible, defensible anchor that is significantly harder and more capital-intensive to replicate (you can't vibe code this combo!), thus protecting the business from direct competition and customer switching.

Mind you: this is a deliberate strategic choice that leverages the tangible differentiation of hardware to build a more defensible and sticky software business, not randomly mixing and "patching" undifferentiated hardware with software.

Anatomy of a HeSaaS-ready workflow

In the section above, I've described the "HeSaaS flywheel": acquire with hardware, lock-in with software, and monetize and defend with an integrated ecosystem that increases switching costs significantly.

Now, can this model be applied to every construction workflow? Clearly, no. You need to identify a specific, high-value workflow that is poorly served by incumbents and disruptors alike, and create a tightly integrated HeSaaS solution that is an order of magnitude better for that single purpose.

It starts with a physical workflow that is fundamentally broken and for which, therefore, the solution must also have a physical component. Does the target workflow suffer from a "hair on fire" problem that originates in the physical world? For example, is the core bottleneck related to inaccurate data capture or a lack of real-time verification? If the problem can be solved with software alone, a HeSaaS model is an overkill. Data-intensive, repeatable, and high-frequency tasks (workflows that are run on many projects, e.g. surveying each building floor) are fantastic for a HeSaaS model. Similarly, frequent and legally mandated compliance and/or environmental logging that rely on tedious manual methods also have potential. In contrast, one-off projects with low-frequency, non-mission-critical tasks make this less appealing: hardware needs to be an essential daily tool to generate the "flywheel" of continuous data capture → software value → customer lock-in → recurring revenue. Without repeated use, there's no data accumulation or workflow integration to create switching costs.

Second, is the hardware component genuinely differentiated on a dimension that customers value (be it accuracy, speed, safety, cost, and/or ease of use)? A commodity device that can be easily sourced or replicated by competitors cannot serve as the foundation for a defensible moat. The hardware must be the sharp point of the spear that wins the initial customer engagement. A strategic consideration here: a HeSaaS device ideally is durable and sturdy enough to keep customers for years, since if hardware fails quickly or is too cheap, recurring lock-in is weakened.

Third is the software component: does it create true lock-in effects? Is the software platform more than just a data viewer or a simple dashboard? To create true lock-in, the software must provide unique analytics, actionable insights, predictive capabilities, or workflow automation that is impossible without the proprietary data stream from the hardware. The software is what transforms a simple tool into an indispensable "operational system" (or better, a system of record). When customers have physical devices deployed across job sites, when years of project data live in your cloud, when entire teams have reorganized their workflows around your platform, that's when switching costs transcend simple inconvenience and become prohibitive.

Data capture (and subsequent processing) is a prime example of a workflow that checks all the boxes for a great HeSaaS model. Here, the primary bottleneck is the slow, expensive, or error-prone process of translating complex physical reality into structured, accurate digital data: current methods often rely on manual measurement or specialized and (very) costly service providers, leading to design errors, rework, and budget overruns. The key to success is a hardware device that is demonstrably superior on a critical axis: speed (completing a scan in minutes vs. days), accuracy (millimeter-level precision), ease of use (one-click operation vs. requiring a trained surveyor), and/or cost (making the technology accessible to a wider market). On the other side of the coin, the software must do more than just store the data: it must provide tools for analysis, measurement, collaboration, and seamless integration with downstream design and construction platforms (and potentially even integrate manipulation, e.g. in a CAD-lite fashion).

In summary, the best-fit workflows are those where hardware is a true differentiator, not just a minor accessory. It should enable something that no software-only solution or generic equipment can.

Now, is this model that novel? Well, not necessarily. Some well-known incumbents have recognized the value of a software + hardware combo decades ago, and are increasingly trying to move more and more from pure hardware companies to true HeSaaS companies. Let's have a look at two examples.

The long road to HeSaaS: journeys from two incumbents

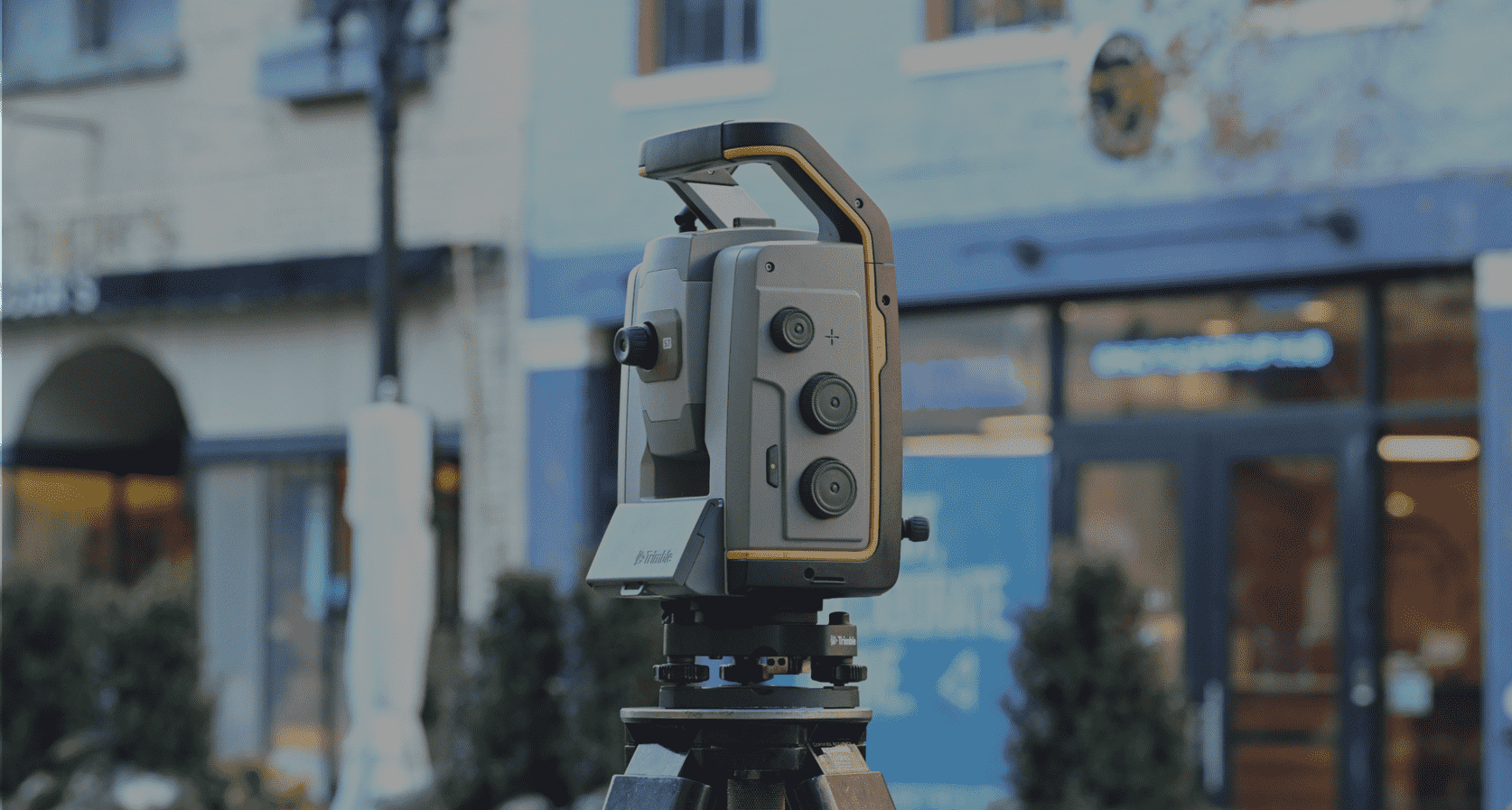

FARO Technologies and Leica Geosystems part of Hexagon are probably well known to a good share of my readers, and an example of "HeSaaS pioneers".

Interestingly, the story of Faro Technologies is one that begins not in construction but in medical devices, with two PhD students developing high-precision measurement tools for orthopedic surgery in the 1980s. This medical heritage instilled their obsession with translating physical geometry into digital data, though they soon pivoted to industrial manufacturing after recognizing the limited scale of the medical market. This pivot culminated in the 1995 launch of the FaroArm, an articulating coordinate measurement machine designed for industrial rigor. Crucially, Faro didn't ship only hardware: the FaroArm launched with companion software called AnthroCAM, establishing an early link between physical measurement and digital intelligence.

The 2000s marked Faro's evolution from a hardware vendor to a solutions provider. This mostly occurred through strategic acquisitions: CATS Computer Aided Technologies in 1998 refined their software into the robust CAM2 Measure program, while SpatialMetrix in 2002 added laser tracker technology for aerospace-scale measurements. By 2003, they'd introduced the industry's first fully integrated 3D Laser ScanArm, combining tactile probing with non-contact laser scanning in a single device. In the 20s, came their push into software and cloud platforms. The 2021 acquisition of HoloBuilder brought a leading platform for 360° photo documentation and progress tracking. This was followed by GeoSLAM in 2022, adding mobile scanning solutions powered by SLAM algorithms.

Today, Faro's hardware portfolio reflects its industrial heritage. But increasingly, this hardware serves as the data capture engine for their software ecosystem centered on Sphere, their cloud platform: field operators capture data with scanners, process it through SCENE software for registration and noise filtering, model it with As-Built plugins for AutoCAD and Revit or verify construction quality with BuildIT, then collaborate through Sphere's cloud platform. Faro also shifted from once-perpetual licenses to time-based subscriptions bundled with updates and support.

However, looking at the financials, we can notice a challenge to this transition. Hardware sales still dominate with 3/4 of revenues, with service sales (including software) taking the remaining quarter.

On the other hand, Leica Geosystems' modern identity began in 1921, when Heinrich Wild revolutionized surveying with the T2 Theodolite, the world's first truly portable opto-mechanical theodolite. The company's current identity came to fruition in the 1997-1998 formation of Leica Geosystems as an independent entity focused on surveying and construction. Their digital transformation began early with the world's first digital level in 1991, but the pivotal HeSaaS moment came with acquiring Cyra Technologies in 2000, marking their entry into 3D laser scanning.

The 2005 acquisition by Hexagon AB accelerated this hardware-software integration strategy. Today, Leica's scanners (from the premium P-Series to the democratized BLK line) serve primarily as data capture engines for their mature Cyclone software ecosystem, an industry standard for over two decades. The workflow is comprehensively digital: Cyclone FIELD 360 manages capture, REGISTER 360 PLUS handles alignment, Cyclone 3DR enables modeling, while CloudWorx plugins integrate with major CAD platforms. Everything feeds into Reality Cloud Studio powered by HxDR, Hexagon's enterprise platform. Ultimately, Leica's platform strategy extends beyond standalone tools: their scanners seamlessly feed Hexagon's machine control systems, asset lifecycle software, and smart city platforms, creating deep ecosystem lock-in.

Leica has embraced flexible monetization with perpetual licenses, annual subscriptions, and project-based licensing, all designed to capture recurring revenue from their software platform. A precise split of Leica Geosystem's division post acquisition are unfortunately not available, but Hexagon's corporate mandate for increasing recurring revenue (showing 7% growth in Q4 2024) indicates their strategic direction toward software and services.

The learning: transitioning from a hardware-centric company to a software-centric one is difficult, particularly when your hardware is your customers' major capital expense (often 5-10+ times the cost of the software). Starting as one doesn't have to be, depending on the hardware you are developing (you just need to be smart in picking your battles).

What about startups embracing this model? Let's have a look at two examples.

Weather stations and laser scanners: examples from disruptors

On the disruptors' side, let me share more about Pavewise and iMapper.

Let's start with US-based Pavewise, which tackles one of construction's most unpredictable enemies: weather. Any paving contractor will tell you that laying asphalt is part science, part art, and largely at the mercy of Mother Nature. Paving contractors have historically relied on regional weather forecasts, which are often inaccurate for a specific job site. An unexpected rain shower can force a complete shutdown of operations, costing thousands of dollars per hour in idle crews and equipment. Conversely, not knowing the precise conditions (e.g. wind, temperature) can lead to poor quality asphalt that fails to meet specifications.

Pavewise's insight was elegantly simple: what if contractors had weather stations right on their job sites? So, that's what the company set out to solve.

Pavewise deploys automated weather monitoring devices that track rainfall, wind speed, and temperature every few minutes, feeding this hyperlocal data directly into their cloud platform. The magic happens when this real-time, site-specific data flows into PavewisePro, their analytical software engine: the platform transforms raw weather data into actionable intelligence. High winds detected? The system might recommend increasing asphalt plant temperatures to ensure proper compaction. Rain approaching one section of a 42-mile project? The software helps managers redeploy crews to dry areas, avoiding costly shutdowns. This transforms the workflow from being reactive to regional forecasts to being proactive based on actual site conditions, preventing expensive operational disruptions and improving quality.

But Pavewise didn't stop at weather monitoring. They recognized another analog bottleneck in the paving workflow: density measurement. Quality control in paving requires constant monitoring of asphalt density to ensure roads meet specifications. Traditionally, this involves workers manually recording readings from density gauges and later transcribing them, a process ripe for errors and delays. In this case, rather than building their own density gauge, Pavewise developed something cleverer: Density+, an AI-powered computer vision system that uses smartphone cameras to instantly digitize readings from existing gauges. The readings are uploaded to an interactive map where roller operators can see density results in real-time and adjust their compaction patterns accordingly.

The Pavewise platform acts as a central hub for all project information. It tracks resources, monitors production goals against bids, manages documents, and provides a shared project map for the entire team. This creates a seamless flow of information from the field to the office, improving communication and enabling data-driven decision-making across the project lifecycle. Weather stations remain Pavewise property through rental agreements, ensuring customers can't use the sensors with competing software. More importantly, as contractors accumulate years of hyperlocal weather data and project performance metrics, the switching costs compound: this historical data becomes invaluable for predicting and optimizing future projects, creating a moat that deepens with time.

On the other side of the pond, Paris-based iMapper targets a pain point familiar to anyone in interior design or renovation: creating accurate floor plans. The traditional method involves tape measures and notepads (and prayers that your handwriting remains legible, and your measurements accurate enough!). A single measurement error can cascade into costly design flaws or construction mistakes. High-end laser scanning solutions from companies like Faro or Leica could solve this problem, but they come with price tags that make small firms wince. iMapper saw an opportunity in this gap, and built in it: their Racer 3 device, priced at around €2k, delivers professional-grade accuracy (±2mm) at a fraction of the cost of high-end systems (and it can scan an entire room in under three minutes with one-button simplicity!).

But again, the hardware is just the entry point. The captured point clouds and 360-degree photos are uploaded to iMapper's cloud platform, where the software processes raw data into actionable insights. Users can merge scans from multiple rooms, take precise measurements directly from the point cloud, and analyze building details that would be impossible to capture manually.

The business model follows a familiar pattern: hardware purchase (with financing options available) plus monthly software subscriptions. Data then creates the lock-in. Every project scanned becomes part of a growing repository of spatial data stored in iMapper's cloud: for firms that have digitized hundreds of projects, the thought of losing access to this historical data makes switching virtually unthinkable.

These are merely two players in what, anecdotally (and gladly), is an expanding universe of HeSaaS companies (shoutout to Groundhawk.io). Now, one reason deterring entrepreneurs from building more HeSaaS ConTech companies lies in the future exit prospects and potential low multiples due to the hardware component. Let's cover this.

Valuation "shenanigans" (can you turn hardware into SaaS multiples?)

Many investors in the past decades have historically shied away from hardware. So did most entrepreneurs. (Kinda ironic, since the initial boom of Silicon Valley was powered by investments in the production and commercialization of physical devices and electronics). But why?

First, because it is inherently hard (it's in the name, after all!). It's riskier, more capital-intensive, has lower margins, has less scalability, etc. On this point, I agree (albeit not fully). However, you have to acknowledge that what makes it hard also makes it very defensible, and defensibility is increasingly more difficult to come by (and therefore, desirable).

Second, most importantly, it's because on top of being hard, it also generally pays lower exit multiples than software (because of non-recurringness, lower margins, etc.). That's also generally true.

But where does HeSaaS stand?

Many might believe it is closer to hardware than software in the spectrum, but I beg to differ. With some shenanigans, I believe you can get valued (almost) as a SaaS business - it's ultimately all about the framing of the narrative and the execution of the software platform. In fact, a HeSaaS startup can fundamentally be a software company that happens to use hardware as a customer acquisition and data-capture tool, not a hardware company with a software feature. For this narrative to be true, it needs to be objectively visible in your financials: your revenues must be mostly recurring (-> strong cohorts) and high margin (akin to SaaS).

This insight can inform how you monetize your hardware + software suite, and the accounting treatment of the hardware itself. Depending on the manufacturing costs of the hardware, you can think of hardware as a CAC (rather than COGS), and structure your contracts with customers as software subscriptions with free hardware. Doing this, your gross margins will be higher, making your unit economics appear much more like those of a capital-light, pure-play SaaS business, and likely command a higher exit multiple. Can this strategy be applied to any piece of hardware? Obviously no.

Indeed, the result of this strategy is that your CAC will obviously increase significantly, so to justify this, you must demonstrate an exceptionally high and durable LTV and your ability to maintain a healthy LTV:CAC ratio, on top of having relatively low hardware COGS. Luckily, the cash outflow problem (of "financing" hardware yourself) is less severe if your contracts are structured as SaaS (and therefore paid yearly in advance).

Is this just some financial engineering? Perhaps, but something to keep in mind! I think this can work exceptionally well for "hidden" niches (overlooked by most) but that need founders with boots on the ground and unique insights to uncover and serve, and for which the hardware component does not cost several tens of $k of dollars to produce.

Additionally, let's not forget that this is a super liquid exit market. If you're disciplined with capital from day one, target profitability early in your journey (very much possible), and crack the right distribution channels that enable rapid deployment, you can build an exceptionally attractive acquisition target in shorter-than-VC timelines and with limited capital requirements. We're talking upper 8/lower 9 figures exits from strategic buyers willing to pay a premium to add complementary HeSaaS capabilities in their catalogue. This means that founders can pursue a deliberate build-to-sell strategy from day 0, raising only necessary capital from partners who understand this game and are aligned with them, and achieve a more controllable yet life-changing exit.

HeSaaS operations playbook: manufacturing, WC, hardware lifecycles

HeSaaS businesses face unique challenges because their hardware components introduce manufacturing complexities that must be addressed from day one. The core strategic decision is whether to manufacture in-house or partner with a contract manufacturer: each path offers distinct advantages and trade-offs.

One thing to keep in mind is that these manufacturing operations are less complex than those for robotic solutions: hardware in HeSaaS generally tends to primarily combine off-the-shelf components (sensors, processors, etc.) in a custom enclosure, which allows for simple assembly operations that can be done manually with minimal equipment. You can have lean, flexible, no-shop floor manufacturing operations and scale them easily (you might have to invest in some CAPEX e.g. for molds, but I don't see these expenses skyrocket). This is a stark contrast to robotics manufacturing, whose complexity is driven by the requirement for precision mechanical assembly of motors, actuators, gears, and joints, often necessitating specialized jigs, fixtures, welding, and quality control equipment for tolerances, plus significantly more complex testing procedures for moving parts.

Therefore, another thing to keep in mind is that for this type of hardware play, differently from robotics, the bottleneck tends to be demand/distribution and not manufacturing (as said: the products are less complex, smaller, easier to make). Hence, it might make sense to first start with a smaller, "no-shop floor" in-house operation and then potentially scale through contract manufacturing, particularly if your product is a high-margin one. If you're afraid of IP leakage, an effective hybrid model involves retaining the most critical and IP-sensitive stages of production (e.g. the assembly of a core processing module) while outsourcing the manufacturing of less critical components or the final box-build assembly.

Also, the "hardware as CAC" model introduces significant working capital considerations (the HeSaaS model, more generally, presents WC needs). In fact, when absorbing full hardware costs upfront while recognizing subscription revenue over multiple years, cash management becomes critical. However, advance payments for annual contracts (fairly standard) substantially ease this strain (e.g. $2,000 hardware unit paired with software at a $500 monthly subscription generates $6,000 immediate cash when billed annually, creating positive day-one cash flow and reducing dependence on external financing). That said, the model's viability still hinges on demonstrating strong unit economics to investors: specifically, that LTV substantially exceeds the potentially initially high CAC.

Last, unlike pure SaaS where you can silently push software updates over the cloud, HeSaaS companies face a unique challenge: physical devices in the field that can't be magically upgraded overnight. When you ship generation 2 of your scanner with 6x faster processing, what happens to the customers still using gen 1? The frequency of hardware releases needs to be carefully calibrated: the key is ensuring that each new generation delivers transformative improvements and not just incremental tweaks. This is especially critical when customers must purchase new hardware to maintain software access (rather than receiving it bundled with their subscription). If all their project data lives in your cloud, forcing a hardware upgrade every 6 months to keep that access feels predatory and will result in customer distrust. This dynamic shifts somewhat under the "hardware-as-CAC" model, where devices are bundled "free" with subscriptions. Here, upgrades become less painful for customers but more expensive for you: another reason to space releases thoughtfully.

Either way, backward compatibility becomes crucial: supporting older hardware generations gracefully, even if they can't access every cutting-edge feature, builds trust and reduces churn. It signals that you view customers as long-term partners, not just "upgrade targets". One way to do this transparently is by establishing clear "EOL" (End-of-life; announces when you'll stop selling a model) and "EOSL" (End-of-service-life; defines when all support truly ends) policies from your first product launch, and communicate these clearly. Ultimately, the goal is to make upgrading feel like a natural evolution.

Alright, time to bring this article home!

Conclusion

Let's recap.

Hardware-enabled SaaS (HeSaaS) combines purpose-built field hardware with a cloud software platform to deliver an integrated solution. In this model, a startup designs specialized on-site equipment that no off-the-shelf alternative can match, and then sells it to customers mainly to enable a subscription-based software service. The hardware "anchor" drives the initial sale, while the cloud software (uniquely compatible with that hardware) provides ongoing intelligence and operational support. You might also bundle the hardware at low or no initial cost, then amortize that cost over the software subscription: financially, this treats the hardware outlay as a customer acquisition expense rather than a cost of goods, which could ultimately give you SaaS-like multiples.

The key in HeSaaS is finding those critical workflows where analog processes create bottlenecks, then building hardware solutions sophisticated enough to digitize that specific data stream (better/cheaper/faster/more intuitively than alternatives). You need workflows in which hardware is indispensable and the data-driven insights are indispensable, too. The value creation happens in software, but the hardware provides the differentiation to win customers, and combined, they create strong lock-in and switching costs.

Ultimately, HeSaaS offers a clear path to building a business with a real competitive moat, exceptionally high customer stickiness, and attractive and predictable recurring revenue. And it does so in a super liquid market.

If you're exploring a HeSaaS model in a hidden-in-spite-of-obvious market, don't hesitate to reach out to us at Foundamental!

More appetite for this type of content?

Subscribe to my newsletter for more "real-world" startups and industry insights - I post monthly!

Head to Foundamental's website, and check our "Perspectives" for more videos, podcasts, and articles on anything real-world and AEC.

#HeSaaS #ConstructionTech #ConTech #AECtech #HardwareEnabledSaaS #Hardware #VentureCapital #BuiltWorld

.png)