When we talk about building materials, most minds immediately go to the heavy stuff: ready-mix concrete, steel, sand, cement blocks, cementitious products. The mental model that follows is usually large infrastructure and/or projects with general contractors as the primary customers.

But the building materials universe is far broader than this, encompassing numerous product categories with entirely different distribution dynamics and customer archetypes that rarely get the attention they deserve.

So, I thought of exploring one such category: (fast-moving) electrical goods. The distribution challenges here are fundamentally different from those in heavy building materials, and so are the opportunities for disruption.

Let’s flip the switch! (expect more such puns)

Mapping the opportunity landscape

The Indian electrical goods sector represents a market that's both large in its current state and expanding at a strong pace. Indeed, India has already become the world's third-largest electricity producer and consumer, creating enormous domestic demand for electrical goods of all kinds.

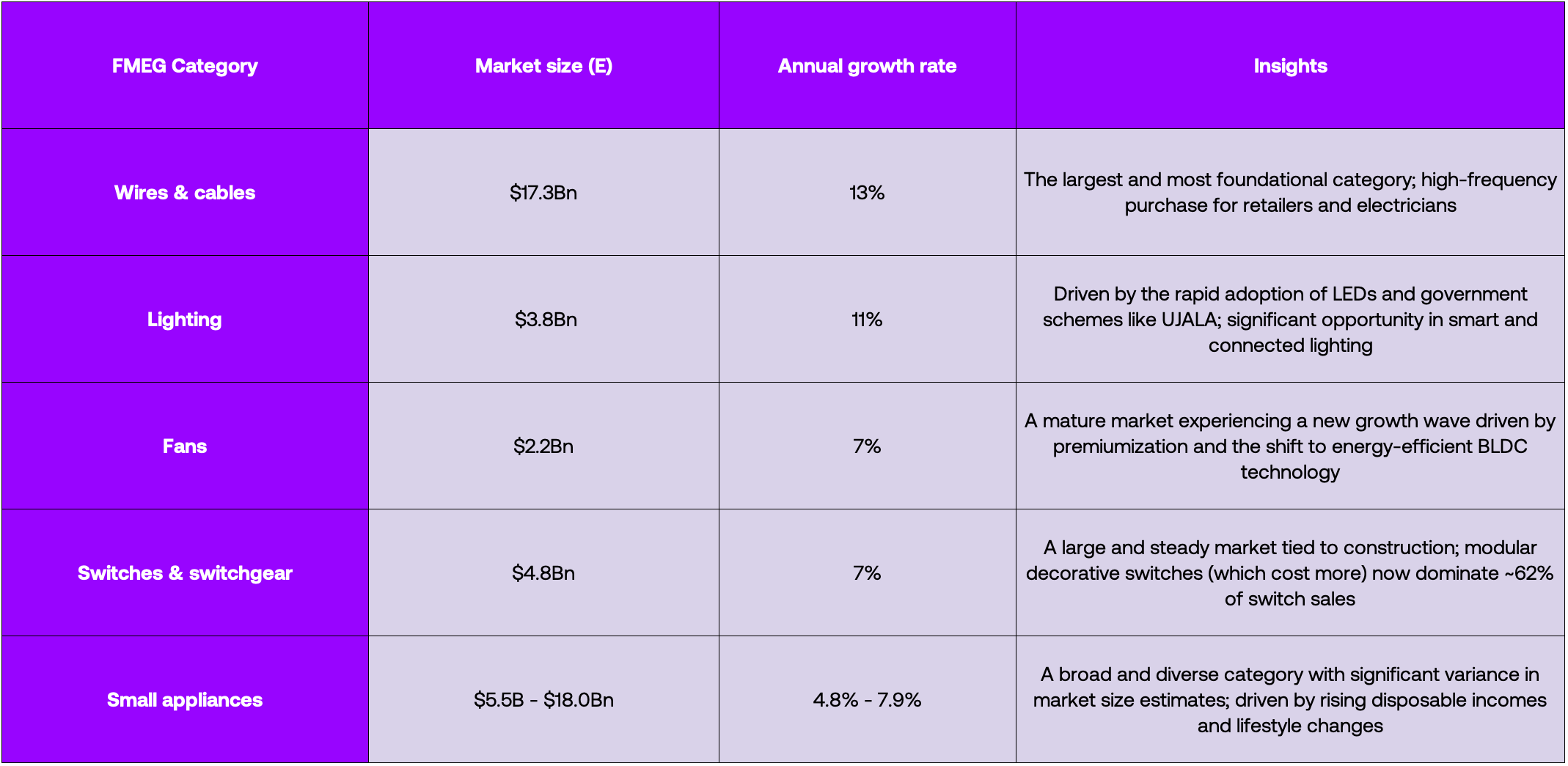

Now, as for most market sizing exercises, the end result depends on who you ask (or where you draw your boundaries). My research shows a market in the tune of $33-49 billion, split across the following categories:

As for all building material categories, the FMEG market does not exist in a vacuum: its growth is intrinsically linked to several powerful macroeconomic trends that are reshaping the Indian economy, and that provide a strong foundation for sustained, long-term market expansion.

The construction and real estate boom stands as perhaps the most direct catalyst. India's urbanization story remains in its middle chapters: with only 35% of the population living in urban areas compared to the global average of 57%, the runway for growth extends far into the future. Each newly built home or building translates directly into a basket of electrical products, such as wires, switches, lighting, fans, and appliances. Public and private real estate development (the latter which has been surging at 20% post-pandemic, although it has more recently normalized) adds strong demand to the market, coupled with a strong post-pandemic rebound in commercial real estate construction. Overall, the Indian real estate sector's projected expansion to $1 trillion by 2030 creates direct, non-discretionary demand for electrical products: every square foot of new construction needs wiring, switches, lights, and more. Government initiatives like the Deendayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana have pushed household electrification to 96%, creating massive new addressable markets in rural India. The Smart Cities Mission drives investment in modern electrical infrastructure, while the Production-Linked Incentive scheme for white goods manufacturing strengthens the domestic ecosystem.

The infrastructure push extends beyond housing into roads, railways, metros, airports, and smart cities - all requiring extensive electrical installations. The National Infrastructure Pipeline's vision of over $1 trillion in investment by 2025 creates enormous demand for wires, cables, and switchgear, with moderate benefits flowing to lighting and other categories. The emerging electric vehicle transition adds another growth vector, with charging station deployment driving demand for specialized cables, switchgear, and connectors.

Additionally, the replacement and upgrade cycle provides a steady baseline demand even in mature market segments.

In summary, the market outlook is bright (literally and figuratively!). A large TAM with robust growth, underpinned by secular trends, provides a favorable backdrop for new distribution models. The pie is expanding, and likely will continue to do so for the next decade, given India's development trajectory. The key is tapping into this growth efficiently, which brings us to examining what's broken in the current system.

Let's dive in (but first, a couple more details on the market structure!).

The market structure duality

The Indian electrical goods market tells a fascinating story of contrasts.

While national brands dominate the headlines and advertising billboards, there's also a different world operating beneath the surface, where regional manufacturers and unbranded products quietly command a good chunk of retail sales volumes across various product categories. However, the market is steadily consolidating, with branded players growing to about three-quarters of the market currently: industry projections also suggest that this organized segment will reach 80-85% by 2027 across most categories. But let's get specific.

Take the wires and cables segment, which forms the backbone of the entire FMEG sector. The top five manufacturers (Polycab, KEI, Finolex, RR Kabel, and Havells) control approximately a bit over half of the organized market. Polycab alone generates over $2.7 billion in revenue, making it India's largest wire and cable manufacturer. These companies have built extensive dealer networks, particularly in urban areas. But here's where it gets interesting: despite this concentration at the top, unorganized manufacturers still accounted for around a quarter of the total wires and cables market in 2024. That's down from 39% in 2014, largely due to GST implementation and growing consumer awareness about safety certifications, but it still represents a substantial chunk of the market.

The switches and switchgear category presents a different picture, as it shows even clearer organized dominance. Anchor by Panasonic has become almost synonymous with basic switches in many Indian households. Havells, through its Crabtree and Standard brands, along with international players like Legrand, Schneider Electric, L&T, and Siemens, control the premium and industrial segments. The organized sector commands about 82% of the switches market (a reflection, I would say, of heightened safety concerns that push consumers toward branded products). Even here, though, regional and unbranded manufacturers persist, serving budget-conscious buyers who prioritize immediate cost savings over long-term reliability.

The lighting category underwent perhaps the most dramatic transformation in the past decade, primarily due to a "LED revolution". Major players like Philips, Havells, Crompton, Bajaj Electricals, and Surya Roshni collectively generated around $1 billion in lighting sales a couple of years ago. Newer entrants like Syska and Halonix have managed to establish themselves despite the presence of these giants. Collectively, the branded segment's share accounts for 67% of the market. Yet even in lighting, that remaining third of unbranded sales tells an important story: rural markets remain flooded with ultra-cheap LED bulbs, often imported or assembled locally with minimal quality control. These products serve a segment of consumers for whom the immediate price difference between a cheap unbranded bulb and a more expensive branded one represents a meaningful choice. The unorganized sector thrives precisely because it understands and serves this price-sensitive segment that larger brands often overlook or deliberately avoid.

The fans category stands out as the consolidation success story. Just four or five national brands (namely, Crompton Greaves, Orient Electric, Usha International, Havells, and Bajaj) control approximately 80% of the market by value. The unbranded segment has shrunk to under 10%, largely because the Bureau of Energy Efficiency's star rating program created compliance requirements that smaller manufacturers couldn't meet cost-effectively. This regulatory intervention effectively accelerated consolidation, pushing out low-quality manufacturers who couldn't invest in meeting efficiency standards. Regional players like Khaitan in East India maintain some presence, but they're exceptions in what has become a predominantly organized market where the category is 91% branded.

The regional dimension adds another layer of complexity. Companies like V-Guard in South India and Rallison in the North have carved out strong positions in their home territories. Or Pritam Switches, a West Bengal-based manufacturer with minimal presence outside its state borders. These aren't small operations, but rather substantial businesses with strong local brand equity, deep relationships with regional distributors, and intimate knowledge of local preferences. What they lack isn't capability or quality: it's the capital and infrastructure needed for national expansion.

Ultimately, each segment of this market (organized national, organized regional, and unorganized) operates with fundamentally different business models: national brands invest heavily in marketing, R&D, and distribution infrastructure, while regional organized players focus on deep market penetration within limited geographies, often achieving higher market shares in their strongholds than national brands. The unorganized sector competes almost entirely on price, operating with minimal overheads and often questionable quality standards.

This ongoing consolidation creates a unique moment of opportunity. Regional manufacturers with strong local brands but limited expansion capital represent an underserved segment (think companies like Starline, Pressfit, or Hifi). They have manufacturing capabilities, local brand recognition, and often produce quality comparable to national brands. What they lack is access to broader markets: traditional expansion would require massive investments in distribution infrastructure, inventory, and working capital. Is this a gap that a digital platform could potentially bridge by offering asset-light expansion paths? Perhaps.

But before we get there, let's take a closer look at the supply chain structure.

The supply chain maze

The distribution of electrical goods in India follows a path common to many other goods.

Products navigate through a complex web of intermediaries, each adding their own margin and timeline, creating a system that's both remarkably resilient and deeply inefficient: a manufacturer produces goods that first move to distributors (typically large entities with significant capital and warehousing capacity, often holding exclusive territorial rights for an entire state or region) or before that, to super stockists; these distributors then supply wholesalers and sub-dealers who operate at more localized levels, breaking bulk and offering multi-brand assortments; from there, products might go through some other layer before reaching the final business customer: the retailer, those ubiquitous electrical hardware shops that dot every Indian city, town, and village; the retailer finally sells to the end consumer, though even here, the actual decision-maker is often an electrician or small contractor who influences the purchase. These individuals represent a distributed sales force with enormous influence over brand selection and product choice.

This multi-layered system achieves impressive physical reach but at significant cost: each touchpoint introduces margin inflation, with products sometimes passing through three or four intermediaries before reaching the final retailer. Information also flows slowly and asymmetrically through these layers, leaving retailers with limited visibility into pricing schemes or new product launches. Physical movement of goods often stretches over several days, particularly for retailers located far from major distribution hubs.

An analysis of the margins reveals why this system persists despite its inefficiencies. Primary distributors typically earn 3-8% margins from manufacturers, with stronger brands offering thinner margins since their products essentially sell themselves. Sub-distributors and wholesalers add another 5-10% to the price. Retailers, sitting at the end of this chain, target margins of up to 20% or more (on unbranded products where the gap between cost and MRP can reach 50%). This happens because price opacity prevails in the market (customers rarely know the exact street price) and because non-branded manufacturers set artificially high MRPs, allowing retailers to offer seemingly generous discounts while maintaining healthy margins.

Geographic disparities compound these inefficiencies. In metros and tier-1 cities, manufacturers appoint multiple distributors and carry-forward agents, ensuring retailers have options and quicker access: electronics hubs like Delhi's Bhagirath Palace or Mumbai's Lohar Chawl allow retailers to source inventory competitively, often directly from company-authorized dealers. Tier-2 and tier-3 towns tell a different story: here, a single official distributor might cover vast areas for a major brand, or there might be none at all. Hence, retailers depend on sub-dealers in nearby cities or maintain relationships with traveling salesmen who visit infrequently. The result is that ultimately, semi-urban and rural electrical shops typically pay 10-15% higher prices than their urban counterparts due to extra intermediaries and lack of direct credit terms. By the time a product reaches a remote rural retailer, its cost has been significantly inflated through the multi-tier margin stack.

The scale of fragmentation becomes apparent in the numbers. India hosts an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 retail outlets selling electrical goods (not including the 12 million kirana stores), ranging from tiny hardware shops to large electrical stores. Serving them are approximately 10,000 distributors and wholesalers, each typically handling one or a few brands. Yet traditional distribution leaves roughly half of all small retailers underserved: about 50% of electrical shops lack direct access to any official distributor, forcing them to travel to bigger cities or rely on ad-hoc local wholesalers, leading to higher prices and inconsistent availability. In this regard, an interesting market adaptation has emerged: larger retailers often double as wholesalers. Roughly 10% of bigger retailers supply 40% of smaller retailers around them. This peer-to-peer wholesaling fills gaps where formal channels fail to penetrate the last mile in semi-urban and rural markets.

Brand preferences also diverge sharply by geography. Urban consumers demand known brands, so city retailers focus on branded products despite slimmer margins. Rural retailers, more margin-driven, happily push local and unbranded goods to price-sensitive customers.

The reality check is that this labyrinthine distribution system, while inefficient, has proven remarkably durable. It achieves broad market coverage through relationships built over decades. Yet its very complexity creates opportunities: every additional layer represents potential for disintermediation; every information asymmetry suggests space for transparency; every geographic disparity hints at arbitrage possibilities.

How can this system be disrupted?

Friction at every layer

Now, in describing the FMEG supply chain, we also unintentionally unearthed some of the pain points for its stakeholders. These inefficiencies and frustrations experienced by every stakeholder reveal why digital transformation isn't just an opportunity, but perhaps more so an inevitability moving forward.

The neighborhood electrical retailer, whether operating from a cramped shop in a city market or a small town storefront, navigates a minefield of operational challenges daily. The most pressing issue is the chronic scarcity of working capital and credit: some estimates show that only a quarter of small shops receive any credit from distributors, and even then, it typically requires several months of consistent dealings to establish trust. The remaining majority operate on strict cash-and-carry terms, forcing them into the informal credit market (where interest rates range from 4% to 8% per month!).

This credit crunch creates a cascading series of problems. Small retailers, particularly those in tier-3 towns, pay 10-15% more for the same products than their big-city counterparts: they lack bargaining power, can't buy in bulk, and often purchase from intermediaries who add their own markup. When they do receive distributor credit, it's typically limited to a single invoice due within 7-14 days, whcih si hardly enough to meaningfully improve cash flow. Formal financing through banks remains virtually nonexistent for inventory purchases, as these merchants are considered too small and lack adequate collateral.

This credit squeeze extends to the retailer's own customers. Local electricians and contractors often purchase materials on credit, promising payment after project completion, so a retailer might extend credit for materials for a project, effectively financing the job themselves. This customer credit, essential for maintaining loyalty and relationships, further strains working capital when retailers can't obtain equivalent credit from their own suppliers.

The procurement process itself becomes a daily struggle against inefficiency. A typical retailer stocks products from 15 or more brands, sourced from multiple distributors and wholesalers. Each supplier relationship requires separate orders, uncoordinated deliveries, and multiple payment cycles. The retailer might need to coordinate with half a dozen different suppliers (e.g. one for cables, another for switches, a third for lights) since no single distributor carries everything. Keeping track of who supplies what, comparing prices, and checking availability consumes hours. Add on top communication lags and opacity that plague every transaction: when a product passes through two or three intermediaries before reaching a small retailer, each layer introduces delays and information loss. Lead times stretch to 4-7 days for out-of-stock items as requests trickle upstream through multiple layers.

Inventory management becomes a guessing game. Many electrical products come with minimum order quantities or bulk packaging (e.g. a box of 20 LED bulbs or a 90-meter wire bundle). Distributors often won't break bulk for small retailers, forcing them to either overstock or go without. With over 25,000 SKUs in the market but limited capital (and space) to stock them, retailers must predict what will sell based on gut feeling rather than data. When a customer asks for an item not in stock, it's often a lost sale. Overstocking is equally dangerous, tying up precious capital in slow-moving inventory that gathers dust on shelves.

Price opacity adds another layer of frustration. As we've seen, there's no standardized pricing in the traditional B2B chain: different retailers pay different prices for identical products depending on their relationship with suppliers, purchase volume, and geography. Manufacturers' discounts and promotional schemes may or may not trickle down fully through intermediaries. Many merchants complain about the lack of transparency in schemes and new product launches. For example, a new LED model or special distributor rebate might never reach all retailers fairly, making it impossible to know if they're getting a competitive deal or if their competitor down the street has negotiated better rates.

On the other hand, manufacturers face their own set of distribution headaches, starting with the challenge of reaching the last mile.

Indeed, traditional networks leave many markets untapped or under-penetrated: companies rely on distributors who may lack the motivation or capability to expand aggressively into smaller towns. Setting up distributors in every small town isn't economically feasible, leaving companies strong in metros and tier-1 cities but with enormous whitespace in tier-2/3 towns. This represents both lost sales opportunities and ground ceded to nimble local brands. Replacing or adding distributors becomes a slow, politically sensitive process as existing distributors fiercely guard their territories.

Brands also have limited direct contact with thousands of small retailers, with visibility ending at the distributor level, which makes executing promotions or gathering ground-level market feedback nearly impossible. Indeed, tracking sales beyond primary dispatch to distributors proves difficult: manufacturers get secondary sales data with significant lag, if at all. This lack of real-time sell-through data hampers production planning and marketing decisions. It also makes counterfeiting and grey market activities harder to control since companies can't trace where products actually sell or identify spurious products entering the system. Moreover, the current system doesn't provide manufacturers with granular insights quickly. For example, if a new LED model fails in eastern India but succeeds in the west, manufacturers might learn this anecdotally months later. Understanding retailer preferences, price sensitivities, and local market dynamics gets filtered through multiple layers, leaving manufacturers disconnected from actual demand signals.

Here's the thing: fragmentation equals friction in this context. Friction in information flow, product flow, and cash flow. Every additional layer, every informal relationship, every paper ledger represents an opportunity for digital optimization.

One could argue that the pain points ultimately aren't bugs in the system, but rather features of an architecture designed for a different time, and now desperately awaiting disruption. So how do you go about disrupting this industry?

Blueprint for disruption

Many of my readers by now probably know we like cloud manufacturing (we've written and talked about it here, here, here and here!) at Foundamental. Looking at the structure of India's electrical goods market, with its increasingly organized nature and oligopolistic tendencies across multiple categories, I fear that the opportunity for a pure cloud manufacturing play here is limited. In my opinion, the market dynamics don't support the typical cloud manufacturing thesis: national brands are consolidating their grip, unbranded/undiscovered suppliers are shrinking, and manufacturing is already reasonably concentrated.

Here, in my opinion, the opportunity lies in reimagining distribution itself. (Note: whether this can command the same premium as a cloud manufacturing model is a question for another day).

In my mind, there are two possible solutions to this problem.

The first approach involves building a "classic" B2B marketplace that essentially sits atop the existing supply chain infrastructure: this model would aggregate supply from various distributors and manufacturers across the SC onto a single platform, offering retailers unified access to multiple brands and categories. Instead of a retailer juggling 10+ different distributor relationships, they could order all categories through one app/portal. This immediately simplifies life for the retailer: one catalog to browse, one cart to check out, and a unified delivery (rather than 5 separate shipments).

The technology layer would handle order routing, inventory visibility across partners, and coordinate fulfillment through third-party logistics. The operational mechanics would work something like this: when a retailer in, say, Coimbatore places an order for Havells fans and Polycab wires, the platform would identify the nearest fulfilling partner for each product category. Perhaps the fans come from a Havells distributor in Tiruppur while the wires ship from a Polycab stockist in Salem. The platform manages the complexity, presenting a single invoice and coordinating consolidated delivery where possible.

The appeal of this option is obvious: minimal capital requirements, rapid geographic expansion, and the ability to aggregate supply across multiple brands. The platform becomes the digital interface that makes an analog supply chain more efficient.

Yet this model faces a fundamental challenge, in my opinion. You're not actually removing intermediaries from the chain, you're simply adding another layer that needs its own margin. The existing distributors (which might be Tier2-3 distributors) still need their (single-digit) margin, while the platform needs its commission, so who pays for that? The retailer. However, the efficiency gains from better routing and inventory visibility might not offset the additional cost layer for them.

To make this work, you'd need to move upstream, partnering directly with manufacturers or primary distributors. But in this case, logistics costs become your enemy. Even primary distributors typically operate regionally, lacking the pan-India infrastructure to make this model viable at scale.

The second, and perhaps more compelling, approach involves building a distributed warehousing network that essentially creates a new tier in the distribution hierarchy, but one that operates fundamentally differently from traditional distributors. Think of it as creating a tech-first super-distributor that combines the reach of multiple regional players with the efficiency of a unified platform, but one that uses technology and financial engineering to scale far beyond what traditional capital constraints would allow.

The operational model revolves around establishing dark warehouses in strategic locations, sized according to their role in the network: spoke warehouses serve as local fulfillment centers covering roughly a 50-kilometer radii - these handle fast-moving SKUs for their immediate catchment areas, ensuring rapid delivery to local retailers. Hub warehouses (substantially larger) serve as regional consolidation points, and are located near metro/Tier-1 cities. Each hub supports multiple spoke locations sourcing directly from manufacturers (important, as you want to shorten the supply chains; at worst from thier one distributors, depending on how "long" the SC is), holding deeper inventory across more SKUs and enabling efficient redistribution across the network. This architecture allows you to serve "spoke warehouses" in tier-2 and tier-3 towns directly, where traditional distributor economics often fail, while maintaining reasonable delivery times and costs.

Owning/controlling the inventory layer creates strategic options unavailable to pure orchestration models: you decide which products to stock, in what quantities, and at what prices. The strategic effects are manifold.

First, assortment control enables market creation for new brands. Regional manufacturers with quality products but limited distribution suddenly gain access to markets they could never reach independently. For the platform, this means favorable commercial terms: extended working capital, better margins, potential equity stakes, or co-branding opportunities.

Second, inventory ownership allows for dynamic market response: when the platform identifies that certain SKUs are moving rapidly in particular regions, it can stock accordingly. Traditional distributors (esp Tier 2-3), constrained by their supplier relationships, exclusive territorial agreements, and smaller capacity, simply can't be this nimble - they're locked into the brands they represent and the economics those brands dictate. A platform with inventory control can respond to actual demand signals in real-time, stocking up on what's moving and avoiding dead inventory on what isn't. The platform becomes simultaneously more responsive to retailer demand and more valuable to suppliers by providing granular market intelligence they currently lack: data on what's selling where, at what price points, and with what velocity. This information asymmetry becomes a negotiating asset in its own right.

Third, and perhaps most critically for unit economics, the model fundamentally restructures value capture in the distribution chain. In the traditional system, products pass through at least four intermediaries. Each layer adds its margin, inflating the final cost while often failing to pass down the benefits of scale or promotional schemes. A primary distributor in a metro might receive volume discounts, seasonal promotions, or year-end rebates from manufacturers. These benefits rarely flow fully to the sub-distributors and almost never reach small retailers in tier-3 towns, who end up paying 10-15% more than their urban counterparts for identical products. A platform with direct manufacturer relationships and its own distributed infrastructure collapses this chain. Instead of three intermediaries, there's effectively one: the platform itself. All the scale benefits that previously accrued only to large tier-1 distributors (volume pricing, promotional schemes, extended payment terms, marketing support) now flow through a single entity that can deploy them strategically. The platform captures manufacturer discounts based on aggregate national purchasing power, not the limited volume of individual regional distributors. When a major brand runs a promotional scheme, the platform can pass those savings directly to retailers rather than having them dissipate or get captured by several middlemen. This restructuring creates genuine economic surplus to distribute. The platform might capture some as margin, improving its own unit economics, but it can pass some to retailers as better pricing, making their proposition more compelling than traditional suppliers. The scale advantages that were previously the exclusive domain of the largest distributors in the biggest cities now become available to the platform's entire network, including retailers in markets where those advantages never previously existed.

This is the core strategic bet: that controlling inventory in a distributed network, rather than merely orchestrating other people's inventory, creates sufficient economic surplus and strategic flexibility to justify the additional complexity and capital requirements. The model works because it doesn't just optimize the existing system, rather it restructures who captures value and how that value flows through the chain.

Now, for this model to be scalable, it needs some financial engineering. The conventional path would require massive capital (either debt or equity), broken down into two distinct components: infrastructure and working capital. The infrastructure piece covers warehouse setup, fit-out costs, etc., while working capital funds the inventory itself, which represents the more substantial and ongoing capital requirement (I mean, it cycles continuously, but you don't want your own equity being stuck in WC for months on end).

Traditional distributors finance this working capital through their own balance sheets or bank credit lines, which fundamentally limits their ability to expand: each new location requires significant capital allocation, creating a natural brake on geographic expansion. A platform can restructure this entirely by bringing in partners who fund the working capital in exchange for yield, such as underutilized warehouse owners. The arrangement would work as follows: the financial partner provides capital to purchase and stock inventory at a given warehouse location; the platform manages everything operational: procurement decisions, inventory management, sales, fulfillment, and collections. The financial partner simply deploys capital and receives a return, e.g. as a percentage of sales throughput or a fixed annuity payment based on capital deployed.

From the platform's perspective, instead of needing to raise and deploy tens of millions in equity or debt to build a national footprint, the platform can expand location by location, with each warehouse funded by partners whose capital is specifically tied to that geography. The dilution impact is dramatically reduced, and the balance sheet stays relatively light. In a way, this mirrors the risk profile of cloud manufacturing: the platform's primary obligation is ensuring sufficient throughput to meet the partner's yield requirements - everything above that threshold becomes the platform's margin. Hence, the platform takes "utilization risk", betting it can drive enough sales velocity through each location to cover the financial partner's returns and generate profit on top. This is fundamentally different from traditional distributor economics, where all the capital risk and all the margin upside both sit on the same balance sheet. The economics work because the platform captures economies of scale upstream (aggregating purchasing power across its entire network to negotiate pricing and terms that individual regional distributors never could), creating sufficient spread between acquisition cost and retail price to comfortably meet partner yields while retaining healthy platform margins. And from the financial partner's perspective, this represents an attractive risk-return proposition, since the inventory itself provides some downside protection (it's physical goods that can be liquidated if things go wrong) and the returns are predictable once throughput stabilizes.

The most elegant version of this model emerges when you find partners with existing but underutilized warehouse capacity, who can therefore monetize idle assets by allocating space to the platform without any incremental infrastructure investment. In these cases, the partnership becomes even simpler from a capital perspective: the partner provides both the physical space and the working capital to stock inventory, while the platform handles everything else.

In any case, the model remains asset-light in the truest sense: the platform doesn't own warehouses or carry inventory on its own balance sheet at scale (apart from, perhaps, the large hubs; this is TBD). Yet it controls the inventory layer strategically, making all the critical decisions about what to stock, how to price, and which markets to serve, getting the strategic advantages of inventory ownership without the capital intensity that traditionally came with it.

Let's now have a look at what you would need to do to succeed in this model.

Execution imperatives

Much of the economic model hinges on capturing upstream scale benefits, which means establishing direct relationships with manufacturers rather than sourcing through intermediaries. On top of getting better prices, sourcing directly from the manufacturers allows you to capture the full range of manufacturer incentives that traditionally only flow to the largest tier-1 distributors (volume discounts, promotional schemes, extended payment terms, etc.). Clearly, building these relationships requires credibility, and they might not be accessible right away - manufacturers need to believe the platform can drive meaningful volume in markets they currently struggle to reach. The problem to solve is demonstrating how the platform can put manufacturer products in front of thousands of retailers in tier-2 and tier-3 markets within 18 months, with full visibility into sell-through data they've never had access to before. For established national brands, this proposition supplements rather than threatens their existing distributor networks, while for regional manufacturers, it offers geographic expansion they couldn't achieve independently.

Now, the value proposition to retailers hinges on product consolidation: "Order everything you need from us instead of coordinating with 10+ different distributors/suppliers, seamlessly and online". This requires breadth across multiple categories (e.g. wires, switches, fans, lighting), and brands (branded vs. unbranded, national vs regional). But breadth creates inventory complexity. With 25,000+ potential SKUs across all categories and brands, stocking everything everywhere is financially impossible and operationally insane. The art lies in intelligent curation and knowing what to stock and where. For example, the top 500-1,000 SKUs likely generate 70-80% of sales in any given region, and it makes sense for these fast-movers to always be stocked in the "spoke warehouses". The next tier (perhaps 2,000-3,000 SKUs that sell occasionally but predictably), makes a great (better?) candidate for "hub warehouses". The longer tail of products might be stocked at the "hub warehouses", or simply not offered at all.

The model works because geographic density (described below) enables frequent restocking runs that keep spoke warehouses replenished without excessive safety stock. When you have several spoke warehouses within 200 kilometers of a central hub, a single truck can efficiently replenish all locations in a consolidated route every 2-3 days. This means a spoke warehouse doesn't need to carry 45 days of inventory across thousands of SKUs, knowing replenishment arrives regularly and reliably. A retailer ordering a less common SKU might not get same-day fulfillment from their local spoke, but they'll have it within 48 hours once the next restocking run arrives. This is still dramatically faster than the 4-7 days traditional distribution requires, and it's only economically viable because network density makes frequent hub-to-spoke logistics runs cost-effective. Moreover, all this inventory flows from a single upstream source (the platform's hub warehouse stocking thousands of SKUs) rather than requiring coordination with dozens of different suppliers and distributors, each with their own delivery schedules and minimum order requirements.

The strategic question is how far to extend the assortment. Pure FMEG is the natural core, but adjacent categories like pipes, plumbing fixtures, paints, and cement could expand the addressable market. Each category addition requires new manufacturer relationships, inventory complexity, and operational learning curves. The right answer likely involves nailing core FMEG execution before methodically adding adjacencies where retailer demand is clear and platform capabilities translate well.

Geography matters enormously in this business, but not in the way most digital platforms think about it - launching everywhere and letting network effects compound doesn't work here. Quite the opposite: success requires building genuine density in each market before expanding to the next. This means resisting the temptation to spread too thin too quickly. The sequencing should be deliberate: establish a hub in a major city, build out x amount (depending on volume) of spoke warehouses in surrounding tier-2 towns, drive retailer penetration in those catchment areas until you hit critical density thresholds, then replicate the pattern in the next region (close to the first one). Density also creates purchasing power concentration. Hence, expansion happens not all at once, but methodically, ensuring each regional network reaches viability before deploying capital to the next. Ultimatley, geographic concentration early on actually accelerates the path to national scale by proving unit economics work and building operational muscle before expanding the footprint.

Last, as we've seen, the fundamental pain point for small retailers is working capital, and they struggle to access credit. Embedding finance is a great way to add a margin layer here: actually, I believe that financial services have to be woven into the core offering. The platform's advantage will lie in doing credit intelligently at scale: traditional distributors extend credit based on personal relationships and gut feel, limiting it to established customers they trust, whereas a digital platform can underwrite far more systematically using transaction data, GST returns, bureau checks, and behavioral signal. This allows extending credit to retailers who would never access it traditionally. If the platform can borrow or raise capital at 12-15% and lend to retailers at 18-24% (comparable to or better than informal credit markets), the 6-10% spread becomes material at scale. The easiest way to do this is through a network of NBFCs or banks that provide the capital and regulatory infrastructure, with the platform handling origination, underwriting, and collections, but eventually, acquiring an NBFC license or building deeper lending capabilities in-house makes sense. Is follows that collections become critical to making this sustainable. This requires field presence for verification and recovery, digital tools to track repayment behavior, and willingness to cut off chronic defaulters despite short-term GMV loss.

Ultimately, this business succeeds or fails on operational execution. The technology needs to work reliably, the inventory needs to be where it should be, deliveries need to arrive on time, and credit collections need to stay current. Retailers will tolerate many things, but they won't tolerate unreliability in their supply chain. That said, technology is important, but it will only get you so far: you need field teams who understand local markets and can build trust with retailers face-to-face; you need warehouse operations that can process hundreds of orders daily without errors; you need logistics partnerships that actually deliver to remote tier-3 locations; you need collections teams who can tactfully pursue payment without destroying relationships.

Ultimately, trust in India's B2B market comes from being dependable and building personal rapport. A tech-enabled model must therefore blend strong digital reliability with human relationship management. Particularly in the "formative years", a company should invest in plenty of on-ground engagement, vernacular communication, and customer education to bridge the skepticism gap.

The winners will be those who can balance technology leverage with human touchpoints appropriately (as for most or all B2B commerce businesses out there, I shall say!).

Some additional considerations

Now, there are a couple of things (namely: tech, private label, and customer expansion) that I haven't really addressed properly in the previous sections, so I'll take the opportunity to do so now.

Let's talk about technology first.

The platform's customer-facing technology needs to strike a balance between sophistication and accessibility. The front-end experience must accommodate the reality that many Indian retailers, particularly in tier-2 and tier-3 markets, are not particularly tech-savvy and may view elaborate applications with skepticism rather than enthusiasm. This suggests that the ordering interface should be remarkably simple, perhaps even rudimentary by the standards of modern e-commerce. An online platform integrated tightly with WhatsApp for Business represents the most natural entry point, given that WhatsApp has already become the de facto communication tool for business transactions across India. Retailers routinely use WhatsApp to communicate orders, inquire about stock availability, and coordinate deliveries with their existing suppliers, making it the path of least resistance for digital adoption.

In this regard, the ordering workflow should also function seamlessly across multiple channels to ensure no potential customer is excluded due to technology barriers: a retailer comfortable with smartphone applications could browse the full catalog and place orders through a dedicated app interface, while those who prefer human interaction could call a phone line to speak with an order-taking agent. Alternatively, retailers could simply send a WhatsApp message listing the items they need, and the platform's system would convert this informal communication into a proper order, generating an invoice and confirmation that gets sent back digitally.

Beyond facilitating orders, the platform could offer retailers a suite of value-added software tools that serve dual purposes: providing genuine operational benefits to the retailer while simultaneously creating switching costs (and perhaps data advantages for the platform). These might include a point-of-sale system that helps retailers generate customer invoices quickly and professionally, simple inventory management tools that track stock levels and suggest reorder points intelligently, or basic customer relationship management functionality to maintain records of their end customers and transaction history. Offering these tools for free (or at best at a nominal cost) would be a strategic move: each additional piece of software the retailer integrates into their daily operations makes the platform more indispensable and more difficult to replace, while simultaneously generating valuable data flows that improve the platform's ability to predict demand, optimize inventory, and tailor its offering to each retailer's specific patterns.

The back-end part of the stack is equally important, as it must also orchestrate the complex logistics of coordinating between hub warehouses, spoke warehouses, third-party logistics partners, and manufacturer dispatch points, ensuring that products flow efficiently through the network and reach retailers within the promised timeframes. This tech should work silently in the background to eliminate the bottlenecks and errors that plague traditional distribution, whether the retailer notices it directly or not.

Now, let's move to the second point: private labels.

In my view, private label should be approached as a complement to rather than the foundation of the distribution strategy: the quality available from established brands like Polycab, Havells, Crompton, and others is genuinely good, and these companies continue investing in product development, manufacturing efficiency, and brand building, plus the market structure, with strong national brands commanding the majority of sales in most categories, suggests that retailers and end customers place meaningful value on these established brands. Trying to build a business primarily around displacing these trusted brands with private label alternatives would be swimming against powerful currents. Therefore, this market might not be the best-suited one for a pure "cloud manufacturing" model, but it doesn't exclude it, in my opinion, from being part of it.

Indeed, large electrical distributors in Western markets have successfully deployed private label strategies to capture additional margin and differentiate their offerings: for example, Rexel, one of the two dominant electrical wholesale distributors in Europe and North America, maintains substantial private label portfolios alongside the major branded products they distribute. The question then is whether this approach translates effectively to the Indian electrical goods market, and if so, what role it should play in the overall strategy. The platform could certainly introduce private label products tailored specifically to the Indian market needs and price sensitivities.

These private-label products, if executed well, could serve multiple strategic purposes beyond just margin enhancement: they create unique SKUs available only through the platform, giving retailers a reason to consolidate more of their purchasing rather than maintaining relationships with multiple suppliers for different product categories; they provide the platform with greater control over its margin destiny, reducing dependency on the terms dictated by major branded manufacturers; and, they offer an avenue to introduce product innovations specifically designed for Indian market requirements. Over time, a portfolio of trusted private label offerings in categories like cables, switches, accessories, and lighting could become a genuine competitive moat, much as private labels have in other distribution sectors.

The prudent approach to executing this strategy treats private label as something to develop gradually as the platform scales and its understanding of market gaps deepens, not as the central pillar of the business model from day one. Early focus should remain on perfecting the distribution mechanics, building density in key markets, establishing credibility with both retailers and major brands, and proving the unit economics of the core model. Private label can then be introduced selectively in categories where the platform has accumulated sufficient data to have high confidence in demand, where contract manufacturing relationships can deliver acceptable quality reliably, and where the margin opportunity justifies the additional complexity and brand-building investment required. It should enhance, rather than define, the business.

Now to the last point: expanding the ICP.

In this article, I primarily focused on electrical retailers as the core customer segment; however, the platform has the opportunity to serve additional customer types who currently purchase electrical goods through various channels: for example, electrical contractors and installers represent one obvious adjacent segment worth considering. These range from small independent electricians working on residential projects to large contracting firms executing commercial or industrial installations. They purchase many of the same products that retailers stock, but often in larger quantities for specific projects and with somewhat different procurement patterns than retailers who maintain inventory for walk-in customers.

Small contractors and individual electricians typically buy supplies on a project-by-project basis, either directly from distributors if they have established relationships and sufficient volume, or from the retailers discussed in this article. The platform could serve these customers directly, particularly when they need bulk quantities or specialized items that small retailers might not stock. Offering them competitive pricing, convenient delivery to job sites, and access to the full catalog without requiring them to visit multiple retail shops could be compelling. Larger contracting firms executing significant construction projects would represent another potential segment, though they would compare the platform's offering against both traditional distributor relationships and the possibility of sourcing directly from manufacturers. Providing them with credit terms and on-site delivery capabilities could win their business, particularly if the platform can offer better service or pricing than they currently access.

Perhaps the most intriguing opportunity involves electrical contractors and installers not merely as customers but as influencers whose behavior shapes broader market dynamics. Electricians occupy a unique position in the value chain as the key decision-makers regarding which specific products get purchased for many installations. When a homeowner undertakes a rewiring project or a building owner needs new electrical installations, the electrician often specifies which brand of wire or type of switch should be used, effectively functioning as the actual buyer even if the homeowner technically pays. This influence dynamic creates an opportunity for the platform to engage electricians directly, essentially digitizing the word-of-mouth and referral sales that drive substantial volume in this industry.

The key is recognizing that while electrical retailers represent the natural core customer segment and the initial focus for building scale, the market structure presents opportunities to expand into adjacent segments that could accelerate growth and increase the platform's value capture once the core model is proven. Small contractors benefit from many of the same value propositions that attract retailers: broader selection, competitive pricing, reliable delivery, and potentially credit access. Electricians represent a leverage point where engaging a smaller number of professionals can influence a larger volume of transactions. Larger contracting firms offer the possibility of meaningful single-customer volume if the platform can meet their service and credit requirements.

Pursuing these adjacent segments makes strategic sense once the platform has established its operational capabilities and proven it can deliver consistently for its core retail customers. Trying to serve too many different customer types simultaneously from the beginning would risk diluting focus and overcomplicating the business before the fundamental model has been validated. However, understanding these expansion opportunities and building with them in mind allows the platform to position itself not merely as a retailer supplier but as a comprehensive solution for the electrical goods ecosystem, capturing value across multiple customer types and transaction flows as it scales.

Alright, time to bring this article home!

Conclusions

The paradox of India's electrical goods distribution is striking: a $33-49 billion market expanding rapidly on the back of urbanization and infrastructure development, yet half of all retailers remain underserved by a distribution system that hasn't fundamentally evolved in decades. Products cascade through multiple intermediaries, each adding margin and timeline. Manufacturers can't reach beyond tier-1 cities effectively, retailers juggle relationships with dozens of suppliers, and working capital remains perpetually scarce for those who need it most.

The question isn't whether this system will be disrupted, but perhaps more so when and how.

Most likely, the answer lies not in building another marketplace that simply digitizes existing relationships, but in fundamentally restructuring how value flows through the chain. A distributed warehousing model might work, one that establishes a network of strategically positioned inventory points that collapse multiple distribution tiers into one. Such a platform could capture the scale benefits currently scattered across various intermediaries while using financial engineering to remain asset-light, bringing in partners to fund working capital rather than raising dilutive equity for every warehouse. Possibly, the solution involves going even further, using inventory control as a strategic lever to introduce new brands, optimize assortment by geography, and embed financial services that address the core pain point of credit access.

The platform that cracks this might look less like a traditional B2B marketplace and more like a new type of "infrastructure" (using the term loosely, here) player, one that combines physical distribution with digital efficiency and financial innovation.

The conditions for this transformation are aligning: the market structure supports it, the technology enables it, and the stakeholder pain points demand it. For those willing to tackle the operational complexity of distributed inventory, the intricacies of manufacturer relationships, and the challenge of winning retailer trust, the opportunity to build the rails on which India's electrical goods commerce runs for the next decade awaits.

The switch is there, waiting to be flipped. (I had to end this with a pun!)

More appetite for this type of content?

Subscribe to my newsletter for more "real-world" startups and industry insights - I post monthly!

Head to Foundamental's website, and check our "Perspectives" for more videos, podcasts, and articles on anything real-world and AEC.

#B2BCommerce #SupplyChain #Distribution #BuildingMaterials #IndiaB2B #ConstructionTech #B2BMarketplace #StartupIndia #SupplyChainInnovation #B2BDistribution

.png)